By Ankur Dang

Public service and celebrating the city’s diversity fuels Van Robinson, president of the Common Council.

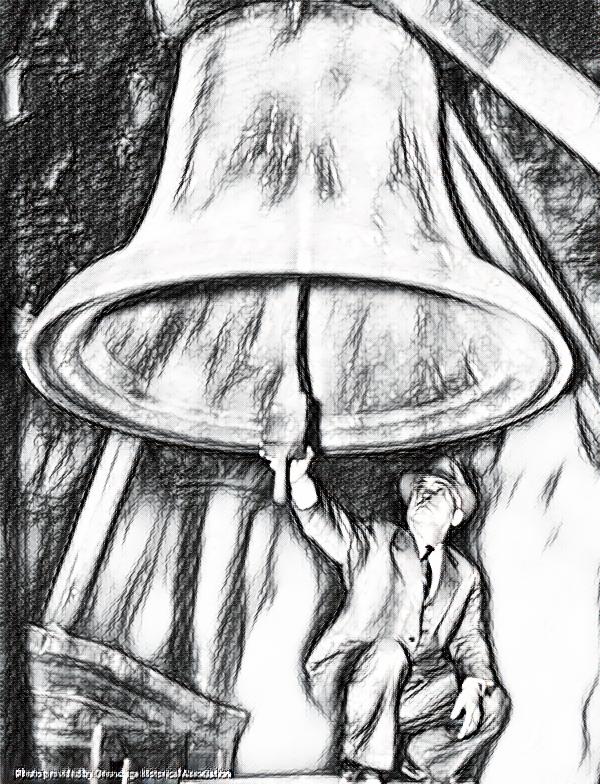

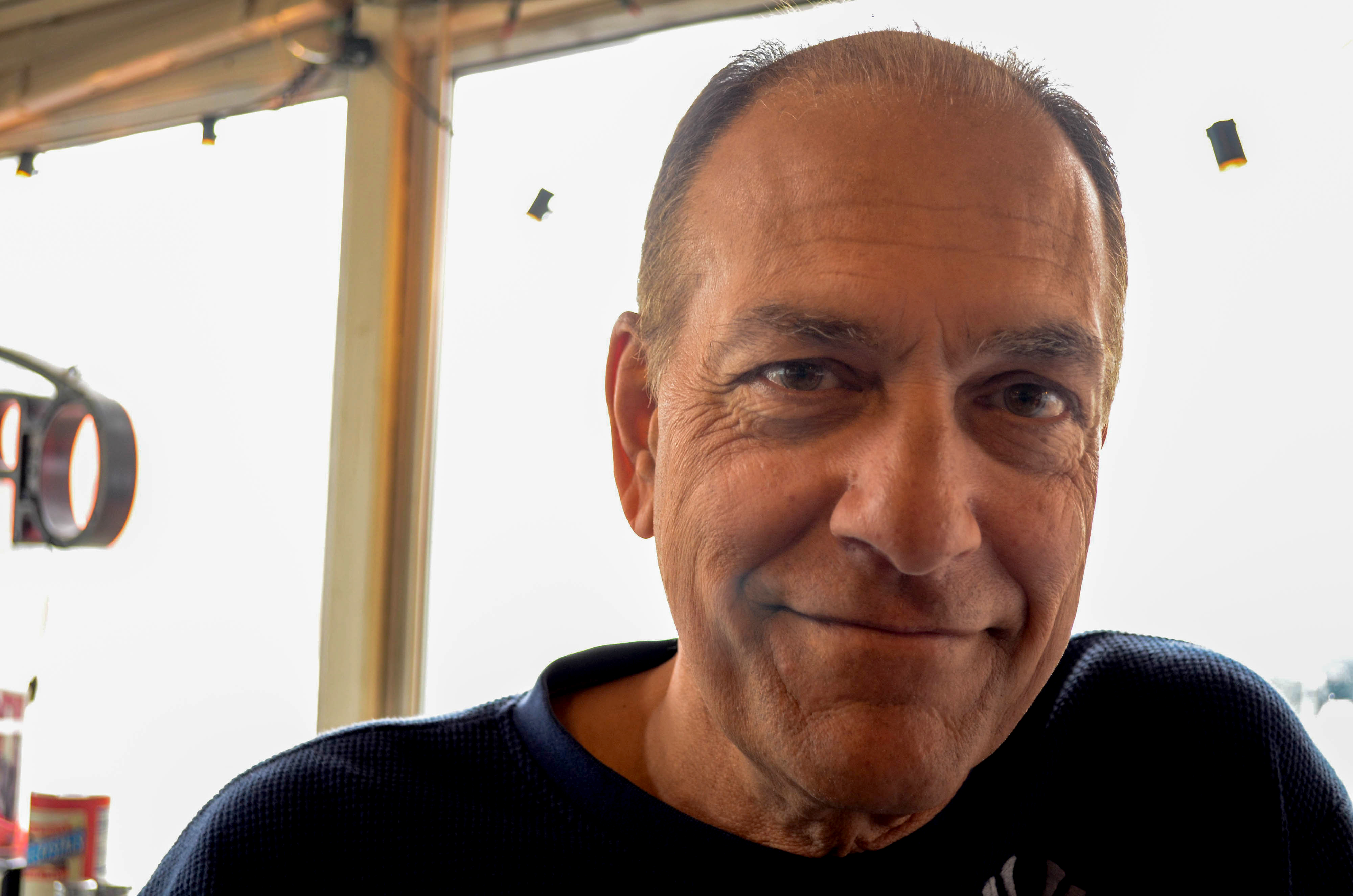

Documents awaiting signatures, requests and letters that need responses, notes regarding meetings he has scheduled for today, and memorabilia from his travels abroad — Matryoshka dolls, bamboo handicrafts, beaded wall hangings —sit on his desk. There is a transparent paperweight in one corner, and his warm, black eyes come to rest on it as the shimmering substance inside the object reflects in the lenses of his spectacles. Van Robinson, the president of the Common Council has seen the sights of the world and found his own place in the service of the people of Syracuse. As someone who has experienced the transformation that America went through in the 60s and the 70s, Robinson’s politics are steeped in social justice and strong positions. Some would say he is a tough leader. But there are many in the city who see a different man behind the title.

Although Kenet Staten doesn’t know the city’s Common Council president personally, he easily describes him as “sweet.”

“At least, that’s what my grandkids would say,” Staten, 49, says with a laugh, explaining Van Robinson’s humility and warm smile makes him an endearing politician. Staten has lived in Syracuse all his life, except for the years he was deployed abroad with the U.S. Army. Today, he is a cab driver and one of thousands of people who live and work in Syracuse. Staten remembers he admired Robinson as a child, because Robinson was responsible for re-starting the NAACP chapter of Syracuse in 1977.

“I know how different things were 40 years ago, and trust me, Robinson does too,” says Staten. “That is why he is more sensitive to the needs of the people of color in this city. And with us being a sanctuary city, there are a lot of them.”

Robinson’s respect for a multicultural society started during his childhood in the Bronx. Then, he joined the U.S. Navy and worked to improve the quality of the Syracuse City School District, using his career to serve his fellow citizens. But it is the “moments in between” that have shaped him as an individual and a public servant.

Robinson recounts how he ended up in the Navy with a fond smile on his face.

“When we are teenagers, we think we are invincible,” he says. “And we were no different. We formed what are today known as gangs. We called them clubs. We wore jackets with emblems on them. Some of us were decent kids, some of us were not. We didn’t use guns, but we had baseball bats and brass knots and such.”

When he was 17, one of the members of the gang killed someone from another neighborhood in a fight with a zip gun. This event prompted Robinson, who had just lost his mother and graduated from high school, to think of his future. He decided that if he wanted to stay out of trouble, he needed to enlist.

So, he served in the Navy for three years, during which he travelled in Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Caribbean. “This was the time of Nikita Khrushchev. Stalin had recently died, and things were changing,” he says. “Everyone was hoping that relations would improve, but they only worsened. In 1962, the Cuban Missile Crisis happened.” Robinson pauses, and in the silence, he seems lost in thought. “Those were dark days,” he adds. “I had left by then. I did not actively participate in any battles and skirmishes, but I saw the world.”

Those travels helped him grow up and informed the person he would become. He met people who spoke different languages, ate foods from other cultures, and saw people who looked different and who prayed to a different God. The experiences prompted him to devote himself to the Civil Rights Movement and continue to grow his worldview. “As a young man of 17, I stood outside the Colosseum in Rome. It did not mean much to me at that age,” he says. “But then I went back as a man of 70, and I was overwhelmed at the thought that 2,000 years ago, gladiators and emperors would have stood there. I was sharing a moment with people from the past, even with my younger self.”

They also continue to inform his activism. Thanks to his continued wanderlust, he now considers climate change a major concern. “Even today, we love traveling, my wife and I,” he says. “And it was on a trip to Alaska a few years ago that I realized just how serious the problem of the climate change is.” He was shaken by a fact that the tour guide shared with them: The stream bed that he and the other tourists were standing on had been covered by the glacier merely five years ago.

Robinson says he is often surprised, amused, and saddened by how people treat each other. He recalls an incident during an official visit to a suburban private elementary school a few years ago. “These three little girls, no older than 8, came up to me and said that they wanted to ask me some questions,” he says. “I thought that they probably wanted to ask me something for a school project.”

The girls had been on an exchange visit to a city school and were concerned that the students there didn’t speak “the proper way.” They also were fascinated to see students dressed in traditional clothes and to see students helping their friends communicate in English. For Robinson, this encounter illustrated the divide between city and suburban life.

Community members like Staten also see this divide and wonder how leaders such as Robinson will address these issues. He values all of the diversity represented in the city’s school district, and he believes the quality of the education needs to be better. “I went to a city school, and it was good when I was a kid,” he says. “But I sent my son to a charter school. Because the public school system is overburdened now. I think we need a shift.”

The school system serves as just one issue Robinson handles that divides the citizens of Syracuse. According Robinson’s chief of staff, Michael Atkins, the other big issue in the city is the Interstate 81. The section of elevated I-81 north that runs through Syracuse along with other bridges located on or near the I-481, I-81, and I-690 interchanges is deteriorating. So much so that the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT) has identified I-81 as a necessary reconstruction project. Robinson has called for the removal of I-81 since 2001 because the highway bisects the city, separating sections of the city and making access to Syracuse University and Upstate Medical University a challenge. At present, the city has four options—replace the highway with a new elevated viaduct; knock down the elevated span and reroute through traffic around Syracuse on Interstate 481 or Interstate 690; dig a tunnel to replace the viaduct; or just do routine maintenance on the existing highway. “That is a big issue because people are just not agreeing upon what might be the best way to have it,” Atkins says. “People in the greater Syracuse area are against the boulevard that will allow the flyover to go from outside the city while residents who live in the city disagree.”

Despite those disagreements, those close to Robinson believe in his ability to help the city work through its infrastructure and education issues. “I have known Van for a long time, I was the council president before him, and he asked me to stay on as his chief of staff,” Atkin says. “He has the interest of the city as his prime concern.”

Robinson’s term ends later this year, and it is unlikely the I-81 issue will be resolved by then. But while he agrees the delay in repairs is not ideal, he believes the concerns are not unfounded. If all this debate and deliberation ultimately leads to a solution that is agreeable to everyone, then it all will be worth it.

As he says that, he pulls up the file on the latest set of requests and questions about I-81. The file holds letters from citizens, activists, and officials and documents. For the next few hours, he will read these and then discuss the best way to go forward on the main issues with the other councillors. His cup of coffee has turned cold. He reaches for the first document, grabs a pen, and begins to make notes.