By Aline Peres Martins

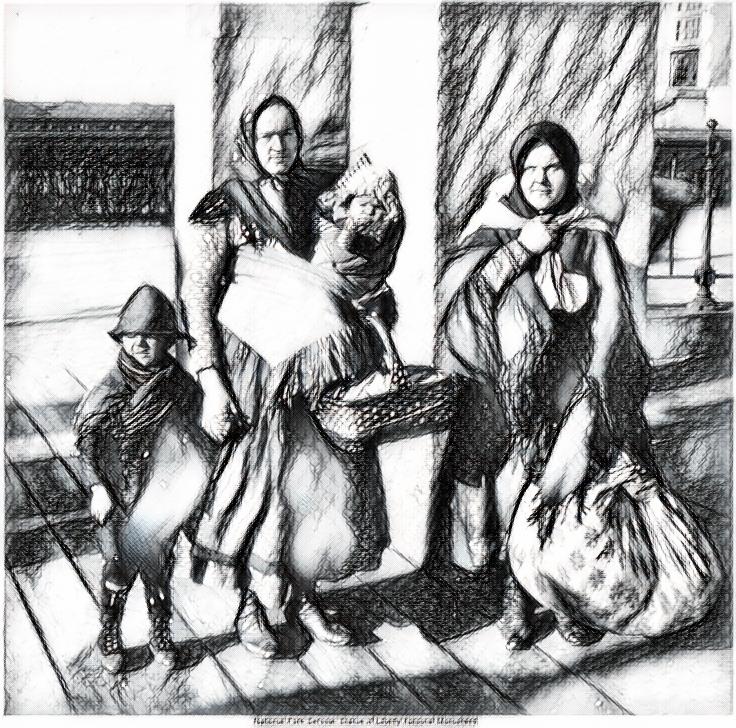

Mary Alice Smothers, the coordinator for the P.E.A.C.E. Inc. Westside Family Resource Center, runs summer programs, workshops, and attends every community meeting.

The room rumbles with voices as community organizers settle into every seat in Fowler High School’s library. A representative from Tomorrow’s Neighborhoods Today (TNT), the citizen engagement organization that facilitates monthly meetings in each of Syracuse’s neighborhoods, stands and tells everyone to quiet down. He introduces himself as Frank Cetera, and then instructs everyone else to introduce themselves as well. Each person offers a quick hello, stating their name and the organization they represent. Then at a table in the back, a freckled, 63-year-old woman, not taller than 5 feet 2 inches, stares at her iPhone through her short, dark bangs and a pair of thick reading glasses, and breaks the pattern. Without looking away from the screen, she barely lifts one hand up in the air and says just two words in a low, husky voice, “Mary Alice.” There’s no need for her last name — Smothers — or the organization she represents — P.E.A.C.E. Inc. — because everyone in the room knows exactly who she is.

Hailing from what neighbors call “the little house of hope,” her co-workers say Mary Alice Smothers possesses the street credibility of a member from the nationwide Hispanic street gang, the Latin Kings. In fact, she says she can’t walk out of her house alone at night without one of the Kings taking notice. “She is well protected. Talk about street credibility,” says Sheena Solomon, the director of the Neighborhood Initiatives at The Gifford Foundation. “You have to be in the community to get that.”

Smothers spends most of her time in the community. She’s served as the coordinator of the P.E.A.C.E. Inc. Westside Family Resource Center for 12 years. More often than not, she can be found in her office on the corner of Wyoming and Marcellus streets, just two blocks down from Skiddy Park and on the edge of the Syracuse Housing Authority developments. Even when the little sign in the window says “closed,” and she’s not there, she’s out in the neighborhood. “I lay my head down here at night,” she says. “I’m here with the drug deals on the corner, the high-speed chases, kids out on the streets — I’m here.”

So, while other community organizations come and go, Smothers remains. “For years we done had people come in here saying, ‘Oh, we’re gonna do this,’” she says, “But all you’re doing is getting money off the backs of these kids and thinking that these are poor people who are dumb and ignorant; illiterate. No, you’re not throwing no crumbs here. It’s not gonna happen.”

That’s why, before doing anything in the Westside, you have to check with Smothers. “She’s the queen bee,” Solomon says. “We hear the voice of the residents through her a lot. And some other people, but she’s the loudest.” While Smothers admits that some people in the neighborhood have told her to calm down, she says, “it’s not about calming down. It’s about seeing these things being done.”

Since Smothers arrived at the P.E.A.C.E. Inc. center, a lot has been done to the building and the programs she runs. Within a month of starting her position, she enlisted her stepson to paint every wall in the building a different color. Smothers doesn’t like sterile, white walls. “When people walk in here, I want them to feel like they’re walking in their home,” she says.

She also started an annual Thanksgiving dinner after she noticed people in the neighborhood spent the holiday alone. She organized field trips to New York City and Washington D.C. for neighborhood children when she realized many kids had never left the Westside. And she created a “pocket park” in front of her house to add to the neighborhood’s limited green space and to invite members of the community to spend time together.

Smothers draws inspiration from people like Ruby Bridges — the first black child to desegregate an all-white elementary school in Louisiana. But this is not because she looks up to her, she says, but because she’s walked in her shoes. She was born a year before Bridges, in 1953, and wasn’t allowed into an integrated school classroom until she started seventh grade. “I sit in the classroom, and I was the only black girl in there,” Smothers says. “When I raised my hand, they would not call on me. I could sit there, and I would have to go to the bathroom so bad and I would not be allowed to go.” But her mother taught her that the way to fight injustice is to speak out. “Holding stuff like that inside will eat you up. This is why I constantly speak out when I see an injustice done,” she says.

Others have noticed this ability. She just received an award from the Human Rights Commission. And Solomon credits Smothers as the reason the Gifford Foundation and the Near Westside Initiative have been able to get the community involved with its activities such as the Multicultural Block Party, Thanksgiving Dinner, Holiday Dinner and Light Contest, Stone Soup Garden, and Community on the Move. But Smothers doesn’t care about awardsl. “I don’t need that recognition,” she says. “That stuff don’t faze me. My mother always said, ‘It’s not about you. It’s about helping others along the way.’”

Smothers’ mother instilled these values in her and her 14 brothers and sisters as they grew up in Maryland, near Washington D.C. Smothers was the middle child, and, she says her mother called her the “worrisome child.” In school, she always stood up for what she believed in. Once, she yelled at her entire class because she noticed they kept making fun of a girl who had gray hair. “I would turn around and throw it back on them,” says Mary Alice. “’I know you ain’t talking to nobody with your nappy head. At least she got hair.’”

So her mother used to sit down and teach her life lessons. And she now tries to pass along those lessons in each of “her kids” — the 5- to 18-year-olds who participate in her annual summer program each June. “I don’t care how far you get, always reach back and bring somebody with you,” she says. “Because the only way you’re going to break this cycle of poverty is by being able to lift another person.”

Pictures of her kids line the walls — performing at dance recitals, graduating from college, getting married. She runs programs for them throughout the year such as a seminar she just organized on reducing neighborhood gun violence, but she also attends their football games, soccer games, and toastmasters speeches. “I have to support them,” she says. “They need that. I done had two strokes and a heart attack. And that’s why I said, ‘God’s not done with me yet.’”

Smothers plans on retiring from her position as coordinator of the P.E.A.C.E. Inc. center next year. But because parents have told her that they will no longer enroll their kids in the programs when she’s gone, she’s thinking about starting her own non-profit. Bill Delavan, who owns the Delavan Center across the street, has offered her a space. She says she’s been “wrestling with the idea.”

But without Smothers in the community, people worry the neighborhood won’t be the same. Dick Ford, who has been teaching free music lessons to children in the Delavan Center for more than 20 years, says he has seen organizations on the Near Westside fall apart. For instance, when former chancellor of Syracuse University Nancy Cantor left, Ford says almost all the funding for the Near Westside Initiative (NWSI) left with her. Not long after, the former director of the NWSI left too.

Ford credits Smothers as the reason he considers P.E.A.C.E. Inc. the most viable organization in the area. He says that because of her, P.E.A.C.E. Inc. is here to stay. “She has activities to keep the kids engaged and not sitting on the street corners,” Ford says. And while he admits no single person can fix all the poverty and violence in the Near Westside, he admires Smothers’ dedication to the neighborhood and her focus on the individuals who reside there. “She can save one life here and there,” he offers. And that is more than most.