President Trump has provoked fear and uncertainty in the hearts of those affected by his travel ban. However, some Syracuse residents are using the ban to inspire hope in their communities.

Words: Sarah Heikkinen

Photos: Alan Taylor Jr.

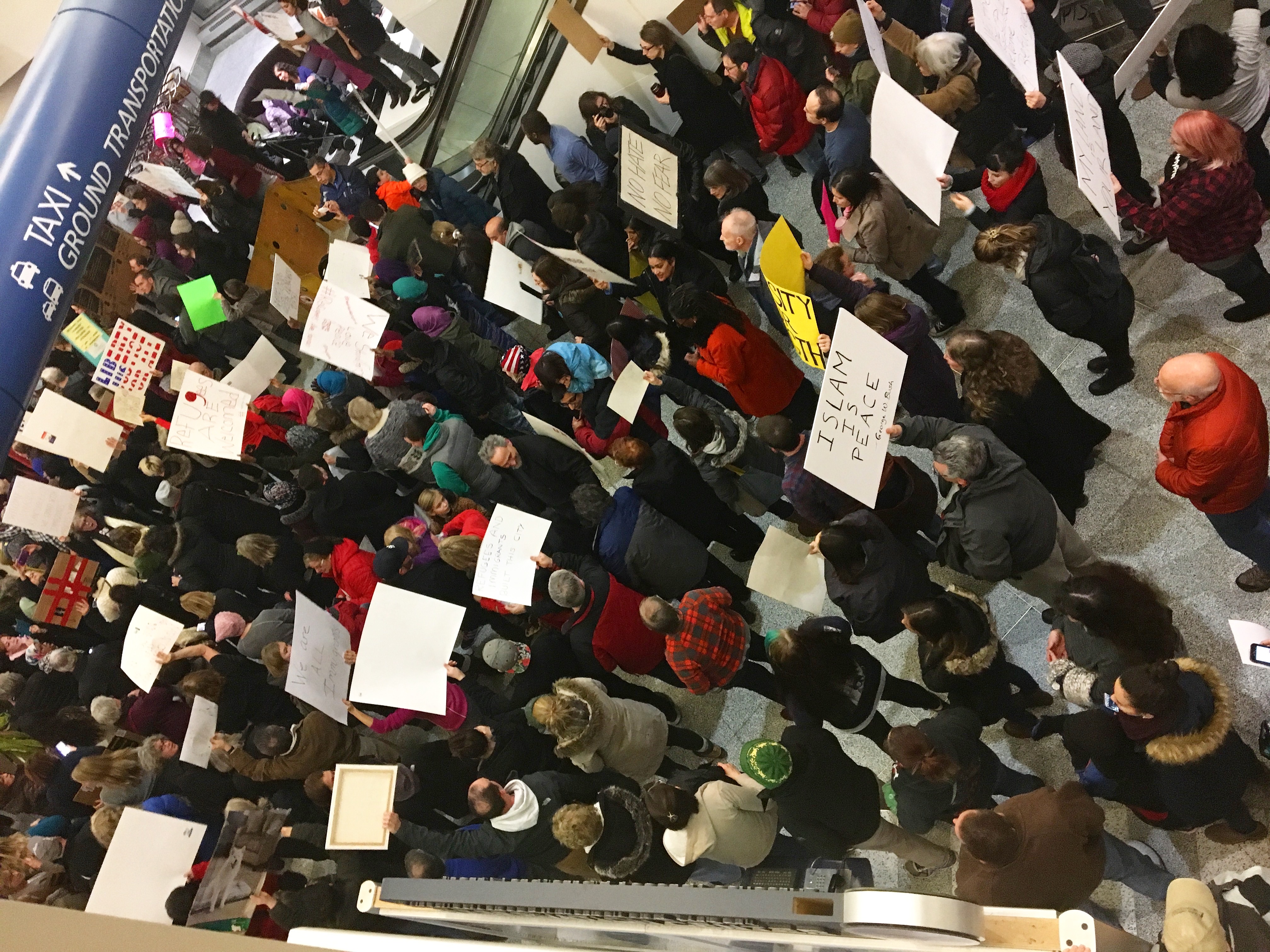

On January 27, 2017, President Donald Trump released an executive order calling for a ban on travel from seven majority-Muslim countries to the United States. The reaction to his proposed ban was swift, with protests erupting across the country over the days that followed. In Syracuse, nearly 2,000 people flooded the Hancock International Airport for a protest organized by the CNY Solidarity Coalition the following Sunday. Protesters demonstrated solidarity with the refugees, immigrants, and legal U.S. citizens being denied access to the United States simply because they were born in Iraq, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, or Yemen.

Across the country, New Americans experienced confusion and fear as they were detained at airports and learned that their friends and family would not be allowed into the country until the travel ban was lifted after 120 days. Khadijo Abdulkadir, a junior at Syracuse University and fierce advocate for refugee rights in the United States, was one among thousands who learned her family in Kenya would not be allowed into the country after years of intense vetting and waiting. They, like Khadijo, are Somalian.

“My aunt and my uncle were in the process for 15 years,” she says. Now, after weeks of calling and emailing the offices of New York Senator Kirsten Gillibrand and Congressman John Katko, Khadijo’s aunt’s flight has been rebooked; her uncle’s case hasn’t gone through yet.

“I had to fight for it,” Khadijo says.

On February 9, 2017, the initial executive order was blocked by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Less than a month later, the Trump administration released a second executive order, removing Iraq from the list of banned countries and asserting that allowing refugees from the remaining six countries to resettle in the United States was a clear and present threat to the safety of the American people.

Despite the Trump administration’s reassurance that these executive orders are not outright attacks on Muslim refugees, the impermeable cloud of paranoia, fear, and hatred surrounding the new administration becomes thicker everyday. Over the course of two months, there has been an increased number of attacks on Muslims and people of color in the United States, regardless of their citizenship or political views. It is a time of uncertainty for many Americans; at any moment, President Trump could unleash another maelstrom of incendiary tweets on the world, or propose another narrowly-targeted ban under the guise of protecting the United States.

But New Americans in Syracuse, like Khadijo, still have hope.

Khadijo Abdulkadir was born in a Kenyan refugee camp in 1994, where her parents settled after fleeing the civil war in their home country of Somalia in 1991. After 15 years in that camp, which Khadijo remembers as being very isolated and unstable, the Abdulkadirs were given the opportunity to resettle in the United States; they were sent to Syracuse.

“I couldn’t speak a word of English,” Khadijo remembers. She now speaks fluent English, and is a year away from completing a degree in international relations at Syracuse University.

Earlier this year, Syracuse Mayor Stephanie Miner declared the city of Syracuse a sanctuary city, meaning it would join several other municipalities across the country in protecting undocumented immigrants and refugees from persecution based solely on their immigration status. Miner’s announcement came just a week before President Trump’s proposed travel ban was released. After its release, many feared for the fate of sanctuary cities like Syracuse, and what could be done to protect those seeking asylum.

For lawyers like Jimena Acuna Smith, an associate at the international law firm Ropes & Gray LLP, the ban presented a huge amount of confusion and chaos. Smith, who has been at the San Francisco office of Ropes & Gray for six years, says that through a company-wide listserv called “Immigration Forum,” she and her colleagues were able to effectively plan how to best help the masses of people affected by the ban.

“It was actually a massive effort and endeavor,” she says. Like many lawyers across the country, Jimena and her colleagues signed up to go to airports to offer pro-bono services to people being detained in the mass confusion following the first executive order, but the list to help was completely full, she says. “The response in the Bay Area was so overwhelming from so many attorneys wanting to help,” she says.

San Francisco, like Syracuse, is a sanctuary city. Jimena says that she, along with everyone else at Ropes & Gray, feels very proud that they’ve had the opportunity to do something.

“I think that the only way to counter this is going to be in court,” she says.

And she’s right. Both of President Trump’s executive orders have been effectively blocked by federal courts, which is part of the reason Khadijo’s aunt will be able to come to the United States.

Khadijo, who like many New Americans has experienced an increase in racism and Islamophobia since the executive orders were released, says she’s not afraid to be vocal about her opposition to Trump’s policies and rhetoric. She’s started a group for refugee women in Syracuse called New American Women’s Empowerment, and she also serves on the board of the Masjid Isa Ibn Maryam Mosque in Syracuse.

“I don’t accept somebody who demonizes others, who puts others in a place that they don’t belong,” she says. “Imagine if I was dying and I knocked on your door, would you let me die in front of you? That’s the kind of mentality that [Trump] needs to understand.”

Khadija Muse, a case worker at the RISE center on Burt Street, which stands for Refugee & Immigrant Self-Empowerment, shares a similar story with Khadijo. In 2005, Khadija and her family emigrated to the United States from a refugee camp in Kenya. Khadija was 10, and neither she nor her family spoke a word of English.

“It got tough,” she says, remembering her father’s struggle to get a job with little knowledge of how to speak English. “There was no one to help them, no one to show them how to get around.” The Muse’s first settled in Maryland, but quickly moved to Amarillo, Texas, as the cost of living was too high. There, Khadija says, life turned for the better.

In the weeks since the executive order was introduced, Khadija says she’s seen an increase in harassment by Trump supporters in Syracuse. A few weeks ago, when Khadija was walking from her car to her house in the late afternoon, a man on her street yelled out, “Trump will get you, he’s coming for you!” A week later, the same thing happened again.

“I wasn’t scared,” she says, smiling. “If Trump wants to get me, he can come and get me because I’m an American citizen and I have every right to be here.”

Khadija is not alone in her experiences with harassment. Just after the travel ban was proposed, Khadijo came home to find that her roommate had torn up her copy of the Quran in their apartment and scattered the pages on the bathroom floor. She has since moved out, but is still experiencing hate online for sharing her story.

“It’s just like, how ignorant can you be?” Khadijo asks, remembering the hateful messages one stranger sent her on Facebook. “Now I understand that I’m literally facing the world, the whole U.S.”

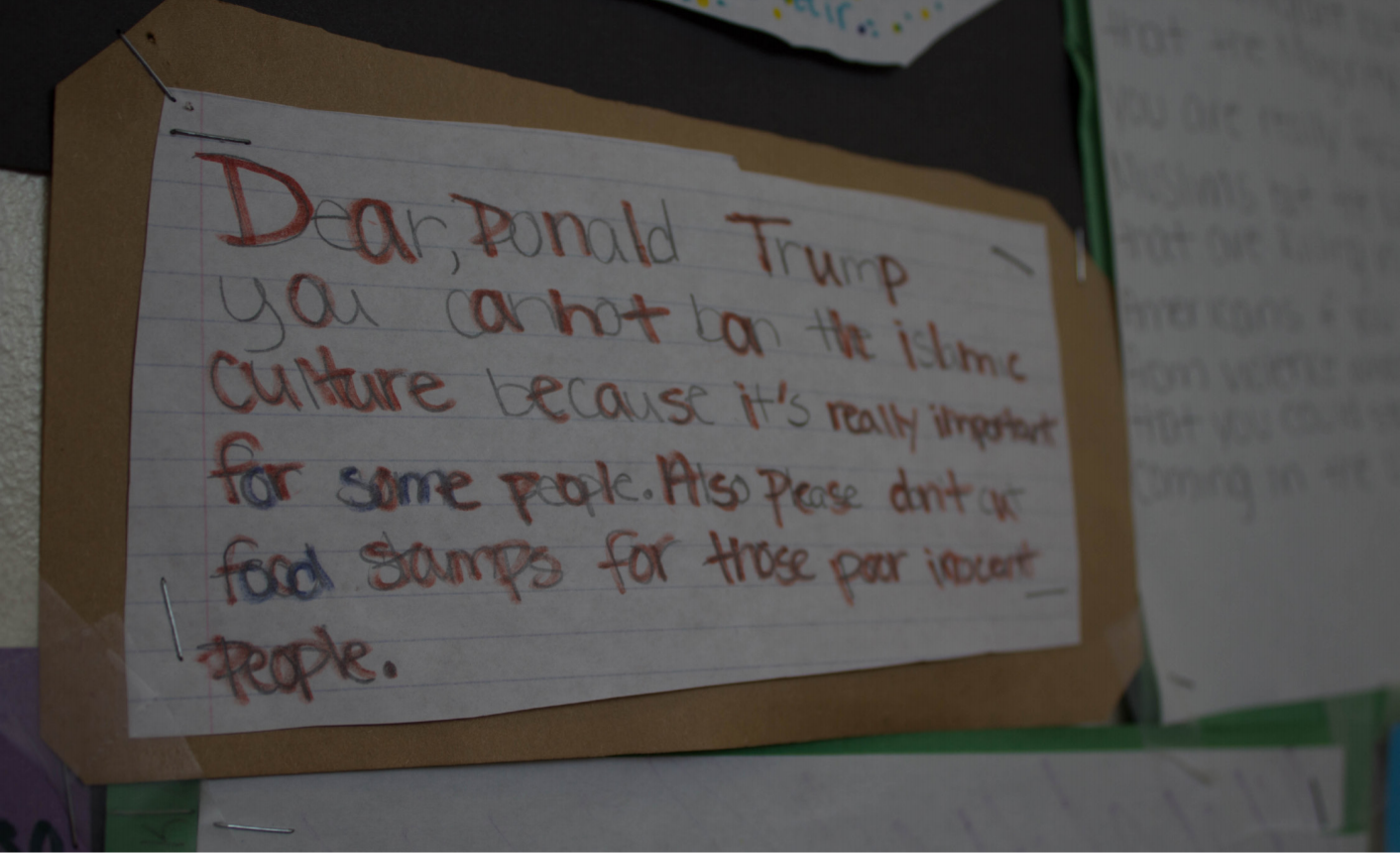

Harassment like this is too often commonplace among New Americans, and not even young children are spared from the vitriol. Rebecca Miller, another case worker at RISE, runs an afterschool program for New American children. She says that the ban has had a strong effect on the children she teaches.

“They’re being called terrorists at school, and when they try to stand up for themselves, it’s perceived as being violent,” Rebecca says.

Because many of the children in the program are young, Rebecca says they may not entirely understand the complexities of the ban, but that doesn’t protect them from the hatred directed towards them.

“These are kids that are just so kind and good, and they’re seeing so much hatred around them,” she says. “It’s sad, because the number one effect I’ve seen since the executive order is a sense of confusion, and for the kids, it’s even worse.”

Despite everything that has happened since the executive order — a day that will undoubtedly be remembered for years to come as President Trump’s first concrete attack against Muslims worldwide — refugees in Syracuse remain hopeful.

Khadija says that she believes that change will come, and that she still has faith in the United States.

“I really have so much faith in the people of America, because I grew up here,” she says. “I know that this is my home, the first home I ever got. The people here are just like family.”

Khadijo, who has been working tirelessly with the CNY Solidarity Coalition to educate New Americans and Syracuse residents on how to combat racism and Islamophobia, says she is deeply moved by the support so many people have shown for her cause.

“It means the world to me,” she says.